Reforming Water Infrastructure – Yosuke Maeda (WOTA)

According to some theories, Europe first started developing modern water and sewerage systems more than 500 years ago. However, there are still people all over the world, including in some parts of Japan, who struggle with issues related to water.

“With how much technology has developed in the modern world, why is it so hard to spread sanitation?” According WOTA Co., Ltd. CEO Yosuke Maeda, that’s a question he has been wondering about ever since his college days.

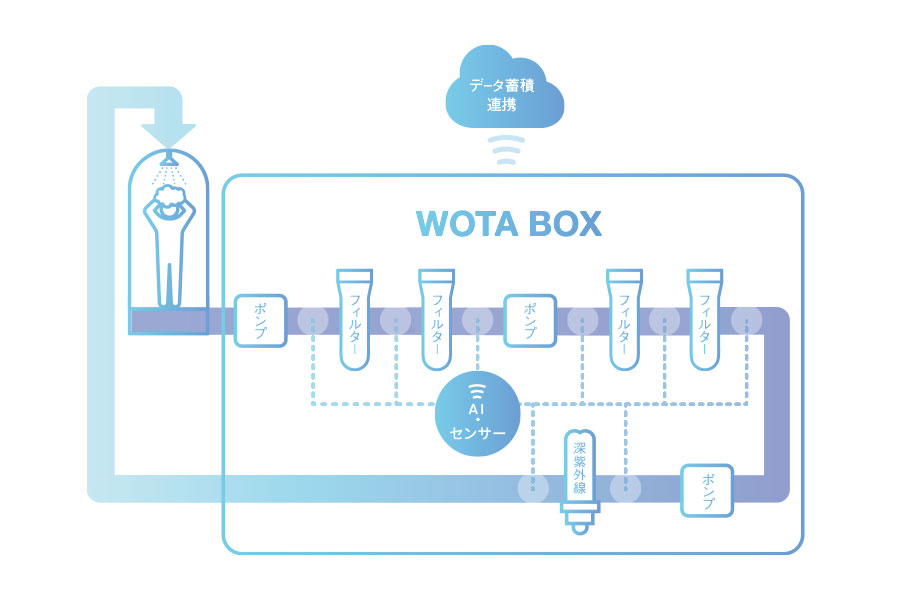

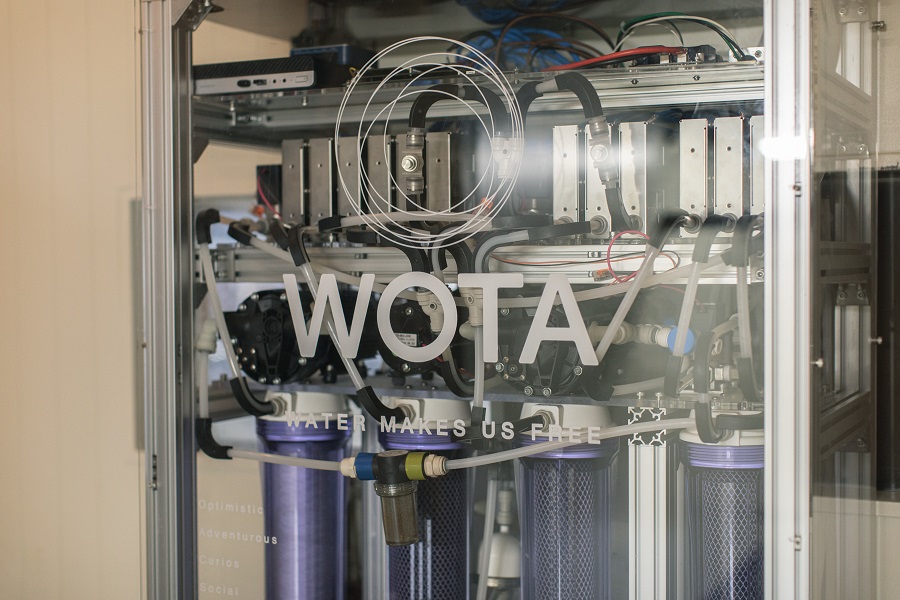

With the vision of “eliminating all kinds of limitations for people and water,” WOTA has developed an autonomous decentralized water circulation system powered by AI technology called “WOTA BOX.” Through the implementation of this product, clean water can be reused within the device without the need to connect water pipes.

This life changing invention received the Good Design award in 2020. It is currently being applied to increasing numbers of applications such as disaster area use and COVID-19 infection prevention countermeasures. In the previous installment, we talked to Mr. Maeda about what kind of impact the WOTA BOX could have on lifestyles of the future.

Moving to Manufacturing Industry Water Circulation Systems

WORK MILL: Could you please tell us about the differences between your WOTA BOX and water services systems used up until now?

Maeda: What we’re trying to do is achieve the water processing value chain which has always been created through a civil engineering model using a manufacturing industry approach. For example, the district heating and cooling system in Nishi-Shinjuku is on the largest scale in the world, and the buildings are connected by ducts and all the waste heat is handled centrally. This is a civil engineering model heating and cooling system which functions with a single large system for the city as a whole to which individual buildings are connected.

On the other hand, is external air conditioning units are used, they can be removed and used in other places when no longer needed. The manufacturing industry model offers the same kind of flexibility as the external units in this example.

This is purely an example, and I’m not saying one of them is necessarily better than the other, but by shifting water infrastructure from a civil engineering model to a manufacturing industry one, I think we can open up new possibilities. Some possibilities are utilizing mass production and providing cheap access to people.

―Yosuke Maeda

Born in Tokushima Prefecture in 1992. Graduated from Tokyo Metropolitan University Faculty of Engineering Department of Architecture, then earned his master degree at the Department of Architecture in the Graduate School of Engineering at the same university. Took an interest in biological research starting in early childhood and conducted an experiment using γ-polyglutamic acid derived from fermented soybeans to purify water and presented the results to The Pharmaceutical Society of Japan during high school. Began working on product and system development for major housing equipment manufacturers and digital art companies starting from his time in undergraduate and graduate studies. Started his own company afterward, and after developing and selling an algorithm for energy conservation controls for buildings, he was hired as the COO of WOTA Co., Ltd. Currently serving as the CEO of the same company and aiming to achieve an autonomous, decentralized water circulation society. Recipient of the University of Tokyo President’s Award for Students, Good Design Award (Prime Minister’s Award), and “30 UNDER 30 JAPAN 2020” award (sponsor: Forbes JAPAN).

Maeda: Think of the process of the automobile spreading throughout the world. Another example is the way refrigerators suddenly became available all over Japan after World War II. Every time people’s lifestyles were transformed in an instant like that, the manufacturing industry was always in the background.

Water services construction up until now has created a water treatment facility in an area separated from the city, then connected the places people live to it with pipelines. However, the environment and land conditions differ for each city. Some examples of these differences include uneven terrain, mountains, and the conditions of roads. Laying out water systems requires new blueprints to be drawn up each time. Once the ground is excavated according to these plans, if stone is found mixed into the soil this stops the construction and a new blueprint is needed for the applicable area.

I have nothing but respect for the people who have carried out these difficult jobs. On the other hand, continuing to build water and sewerage systems in mountainous areas isn’t realistic as Japan’s population continues to dwindle through the next 100 years. I feel that the time is coming to consider a new style. We are getting an increasing number of inquiries from municipalities struggling with financial challenges related to maintaining their water and sewerage systems.

Maeda: What we are working on is to replace the operation management of the water treatment plants built up by our predecessors with digital technology. In addition, we are creating models of the individualized operation management technology used up until now to preserve it. It sounds extreme, but what I want to do is make water treatment systems like home appliances. Using the same common specifications and mass production, we can reduce the cost.

“Why are you in the water treatment business in modern Japan?” That’s a question I get a lot, but there’s plenty of synergy. There is no other country with water treatment technology standards as high as Japan’s right now, and the foundations for the manufacturing industry are already in place.

Why Are iPhones Common, and Water Treatment Not?

WORK MILL: Mr. Maeda, you took on the role of CEO at your company in 2020. Were you already focused on the ideal form of water systems even before that?

Maeda: I’m from Tokushima Prefecture, which has the worst water and sewerage accessibility of any of the 47 prefectures, and there were lots of areas without either running water or sewerage services in the western part of the prefecture where I grew up. That also caused me to see availability of water and sewerage services as one of the differences between the city and the countryside.

There was much demand and many discussions made around me to build more water systems. In the midst of this, I had the chance to see the process of building these systems and experienced how difficult the construction is. Things like how you have to avoid any buried rock you find and that there’s no way to know where a rock could be without digging are some examples of this.

They say the first modern water and sewerage systems were created more than 500 years ago. However, in spite of the fact that water is absolutely essential to daily life, there are still places in the world without access to these systems.

On the other hand, it took only around 10 years for smartphones to reach the farthest corners of Africa. I visited the village of the Maasai tribe in Kenya at the end of 2019, and they had 4G service and battery solar systems there. Everyone was using smartphones like it was the most normal thing in the world. And yet, they still travel long distances to reach wells where they can collect water.

WORK MILL: So you pondered the simple question, “Why can’t the problem of water access be solved?”

Maeda: Something else happened that caused me to see the question in a more abstract way. On March 10, 2011, when I was notified of my acceptance to university, I moved to Tokyo. The Great East Japan Earthquake happened the very next day. Then we lost water because of the earthquake. I was struck by how weak the urban infrastructure was and how different the city people’s attitudes toward water were. Even with water services stopped, no one tried to use water flowing in nearby rivers, and no one even knew what that water could be used for.

In my hometown, everyone knows the quality of the water in the rivers and they pay attention to it, thinking “if something happens we can use this.” When we have fresh vegetables in the summer, people think “the water over there is cold, so let’s chill them in it.” If you’re out walking in the mountains and get thirsty, people know that “the water flowing from the mountain surface over there tastes sweeter than the water here.”

In the city however, no one thinks about these things at all, and the only connections people have with water are buying bottled mineral water from the convenience store. People really don’t look at the Kanda River and think “I’d like to use that for something.” That experience caused me to start thinking about people’s relationships with water.

A Form of Water Treatment Designed by People

WORK MILL: Could you go into a bit more detail about people’s relationships with water?

Maeda: Our company name “WOTA” refers not to ordinary water, but instead to “water designed by people.” Water treatment up until now has been conducted at places separated from cities, removing impurities while place a burden on the environment, a structure of pushing problems outside. The water treatment approach we hope for is one in which people can freely control their water. But this doesn’t mean water will simply be wasted. After all, that wouldn’t be a sustainable approach.

We’re aiming for water treatment designed for people that provides freedom through water access alongside the sense of responsibility that goes with it.

WORK MILL: I see. More specifically, what kind of water treatment conditions will you achieve?

Maeda: One of them is freedom from layouts and phases. In other words, “anytime and anywhere.” Although water service facilities were dependent on pipelines up until now, what we are aiming for is enabling water to be used in any location, whether it’s in a city, inside a building, or out in nature. Also, the system will work in normal times, emergencies, and disasters, regardless of external circumstances. I think this is the way lifelines should be, and our autonomous decentralized water circulation system will make it a reality.

WORK MILL: Based on your track record of providing clean water to disaster areas, your company’s product is thought to be something for emergencies, but that isn’t the case.

Maeda: Well, I do believe that disasters can inspire people to rethink the importance of the interrelation of nature, water, and human society. We think they are one of the reasons that municipalities are thinking about the future of their water systems. That’s why, in addition to handling urgent disasters, we want to consider the future of water moving forward in both disasters and normal times together with local governments.

Also, the initial product plan was something completely different. We were aiming for a shower box product that can be installed in an office without any construction originally. In the summer of 2018, we conducted verification experiments at 100BANCH and other facilities. However, there was severe flooding in western Japan immediately after that, so we split up the product and provided it for use in the disaster area. I realized a lot of things at that time.

When I went to an elementary school in Kurashiki which was being used as an evacuation site, there were about 200-300 people there, and some of them had been unable to bath for a week or more. However, there was a pool nearby. That made me wonder, “Why don’t they use this water?” However, the local people said, “Please, help the children, mothers, and elderly people bathe.”

At that time, I realized that even though there are lots of people who want to resolve these problems with water, there are issues such as a lack of methods for revolving them, or a perceived lack, which are preventing progress. I decided that in that case our WOTA BOX should aim to be a tool which can assist these people in solving their issues with water services. These experiences led to our current product development approach.

Pay Attention Not Only to Changes but What Stays the Same as Well

WORK MILL: Talking with you, I got the sense that this project is an extension of your own personal experiences. It’s not like you were seeking out business opportunities, then focused on water afterward. The order is different.

Maeda: In the end, I don’t think we’re trying to invent something outlandish. By thinking honestly and simply about a single theme and considering which way to progress at each juncture, the resulting specific framework is the creation of something that never existed before.

“Why is this problem occurring?” With awareness of that simple question, we shift our mindset and think instead, “Why are things that can be done in other areas impossible here?” This involves the irrational, unreasonable, and inefficient aspects of the problem. At WOTA, this starts from considering the question, “Why are water services the only ones that don’t spread?” I think that’s the fundamental framework for my mindset.

WORK MILL: We are in the midst of a period of drastic changes. Do you have any thoughts on how best to face these changes?

Maeda: I think what’s important is to face the world in your own way and set constants and variables for important matters. The world is constantly changing, and I think about not only what’s changing but also what stays the same. Then I consider what happens if I set a hypothetical constant. What if something I’d thought was a variable up until now was actually a constant? If I’ve actually found a constant that will remain unchanged in the future, that’s probably a highly-important element that’s a priority for people.

There are similarities with the mountains where I grew up. Although the overall structure of the mountains stays the same, changes occur day-by-day in smaller areas. There’s a certain rhythm to single tree branches breaking, and when the sunlight hits the ground beneath, the vegetation shifts from shade-loving moss to sun-loving moss in about a week. Walking over that surface, the texture under your feet is different from before. I’ve had an interest in those sorts of complex systems going way back.

The brain is limited, so it’s impossible to recognize and be aware of all ecosystems. I think in my case, that thinking style of paying attention to what changes and what stays the same, then setting variables and constants may have started back then.

***

This is the end of Part 1. In Part 2, we discuss the possibilities for the “WOSH” hand-washing stand installed in the WOTA BOX. Coming soon!

Updated: September 1st, 2022

Interviewed: June 2021

Images credits: WOTA Co., Ltd.

Text: Press Labo

Photos: Shinsuke Yasui