Why 40,000 people Visit Our Waste Treatment Plant Each Year – Noriko Ishizaka From Ishizaka Sangyo, Japan

Home to numerous industrial waste incinerators and treatment plants, Kunugiyama, a mixed forest which extends across the cities of Tokorozawa, Kawagoe, and Sayama, and the town Miyoshi, was once called The Ginza of Industrial Waste.

In 1999, erroneous media reporting led to an uproar about dioxins in Japan. Against a background of intense finger-pointing at industrial waste management companies, there was one industrial waste company with a rather off-beat story about attracting fireflies and Japanese honeybees. That company was Ishizaka Sangyo Co., Ltd., based in the town Miyoshi.

In Japan, waste is roughly divided into two categories: one is general waste, which is generated by citizens living their lives, and the other is industrial waste, which is generated by economic activity.

While the cost of general waste processing is covered through taxation paid by citizens, this is not the case with industrial waste, the processing of which individual companies outsource to external companies. Ishizaka Sangyo handles this kind of industrial waste processing.

Ishizaka Sangyo takes the industrial waste that has been trucked to its plant and carries out the recycling (resource recovery). It now has a solid reputation for being a high-tech industrial waste plant that has achieved an industry-leading 98% recycling rate.

Interestingly, inspection groups visiting Ishizaka Sangyo come not only from industrial waste companies, but from a wide variety of fields, including educational institutions and manufacturing companies. It seems that visitor numbers are as high as 40,000 people a year. We are pleased to share our in-depth conversation with the company’s representative director, Noriko Ishizaka.

Many Visitors Come To Find Out About our Staff Rather Than the Garbage

ーNoriko Ishizaka

Born in Tokyo, 1972. After graduating from high school in Japan, she studied at a university in the US for a short period of time. She joined Ishizaka Sangyo Co., Ltd., which was founded by her father, in 1992. Motivated by an incident of erroneous reporting about dioxin contamination of agricultural crops in the Tokorozawa area of Saitama Prefecture, she negotiated directly with her father saying, “I will be the person who changes the company,” and was appointed president in 2002.

WORK MILL:Ishizaka Sangyo is said to be visited by up to 40,000 people a year from all manner of industries. What are the aims of the people who come to visit you here?

Noriko: As we are not engaged in direct sales, there aren’t so many opportunities for people to learn about us. So for the most part, people come to know about us through word of mouth, and the message that gets around is that we have lovely people working for us. The focus is on our employees rather than on something like having excellent technology or a wonderful president.

Industrial waste management tends to have a negative image, don’t you think? There is still a strong perception of it as an industry that no one wants to work in; an industry with a bad reputation. So, can you explain why—in the face of all that—our employees seem to do their jobs so happily? Corporate people come to visit us with such questions in mind.

WORK MILL:We certainly got the impression that you have a lot of lovely staff here. The parking lot guides and people at head offices greeted us with a smile each time they passed by. What kinds of in-house initiatives do you have?

Ishizaka Sangyo’s Future-oriented Work Style. Garbage Is Not Garbage, It Is Resource That We Connect to Future.

Noriko: Before going into such initiatives, please let me explain the current state of affairs in the industrial waste industry. But first, let me ask you about your fundamental image of the industry.

WORK MILL:I think I have quite a few impressions about wages not being very high despite the severe working environment…

Noriko: That’s true. My father founded Ishizaka Sangyo, and I joined the company to help him out. I remember in those days when I was new here, all our customers were saying “I want you to reduce treatment costs. I don’t want to spend money on something I’m going to throw away.” But on the other hand, you have an extremely harsh working environment, and when you think about the time and effort required for the processing, the cost and the actual state of affairs were completely out of proportion.

WORK MILL:I think everyone shares the feeling of not wanting to spend money on things that they’re going to throw away. Even at the individual level, there are lots of people who will do whatever they can to avoid having to spend money on the disposal of items they’re not going to use anymore.

Noriko: Well, that doesn’t sit right with me. And that’s because industrial waste disposal is absolutely indispensable in this world. Without industrial waste disposal, there’s nothing that we can do but create landfill, but this is environmentally destructive.

Nevertheless, industrial waste management companies are the target of criticism because the public takes zero interest in waste management. Back in 1999 when all that strife about dioxins was happening, we ended up getting attacked, despite having taken measures in advance.

When things like that happen, staff working at the plant end up thinking in a very low-level way. As I’m sure you’ll agree, dispassionately working your way through the garbage that’s sitting there in front of you is an everyday kind of job where the focus is on what’s right there, and it can’t be particularly enjoyable.

WORK MILL:How do you get people to work with their focus on the future, rather than on what’s in their immediate field of view?

Noriko: I think that if you’re sharing future-oriented work styles with employees, their job becomes enjoyable if they can see there is “a path for us to follow.” That’s why I launched into the task of creating this kind of company.

The first area where I felt awareness was needed was the idea that garbage should not be treated as garbage. I felt that certain perceptions held by people outside the industry are not right: that waste is rubbish and that an industrial waste company is one that disposes of garbage. For me, waste—all of it—is a resource. All of it should be recycled and given a new life.

I’d like to look at things as a larger framework, of products that humans make for other humans as a “biosphere,” and doing so, to redefine manufacturing. I think it is only us, an industrial waste disposal company, who are in a position to say something like this.

WORK MILL:What kind of initiatives did you take in changing your image for people outside the company?

We Cop Criticism Because People Are Unaware of What Actually Goes On. Well, if That’s the Case, We Should Have an Open Factory.

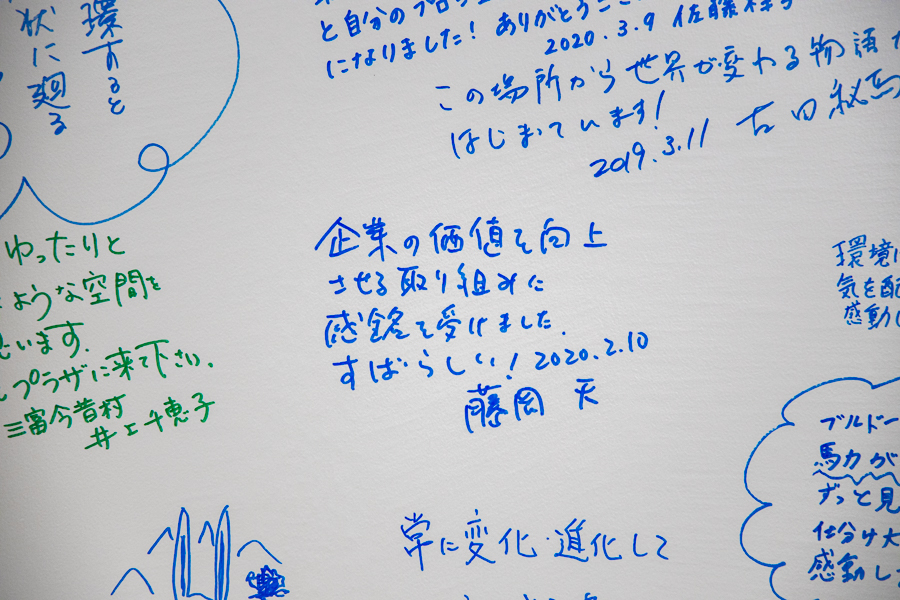

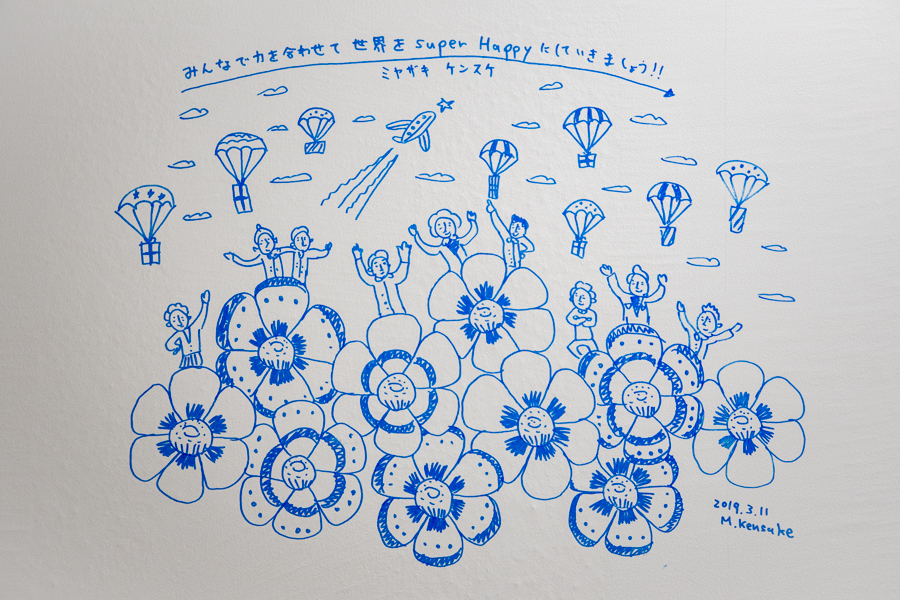

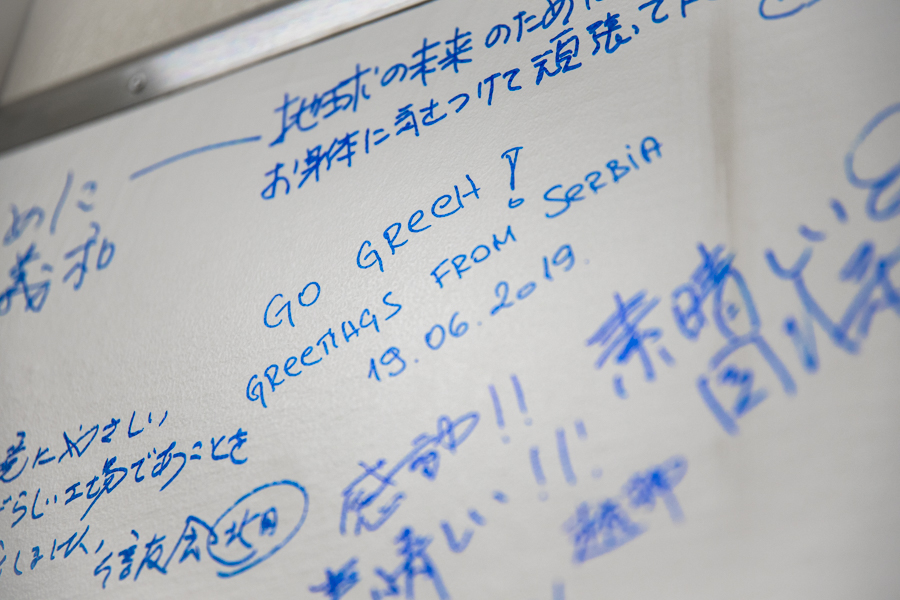

Noriko: In changing our image for people outside the company, I often use an expression: “making our sentiments visible.” What someone is thinking is not visible to the eye, right? So I’ve put a lot of effort into this area. Opening up our processing plant to the public was one example of this.

We want to promote understanding of the work that we do by having people come and see what actually happens in the plant and with waste materials. Meanwhile, listening to our visitors, we are able to gauge how much they think about waste.

WORK MILL:Is your opening up the plant related to the 1999 uproar about dioxins that you mentioned earlier?

Noriko: Two years before the dioxin incident, we had, in fact, already installed a new incinerator with anti-dioxin apparatus. This was breakthrough technology, so much so that it actually became a talking point in the industry.

However, the general public doesn’t care about technology. Of course, there’s hardly anyone who understands the technical stuff; people don’t even know that a lot of money has been invested in it. We just copped flak because of the simple fact that the incinerator had a chimney.

To be honest, I think the sense of dissatisfaction and unease about industrial waste treatment plants has its origins in the low level of interest in the amount of waste Japan produces each year and the ways in which that waste is processed. People get a sense of unease about things that they don’t understand. It’s because of this that I felt the need to give outsiders the opportunity to learn more about what we are doing.

WORK MILL:So, despite the fact that your work is absolutely necessary for society, people outside the industry are not getting the message about the way things actually are. And you opened the plant to visitors as an embodiment of your idea of making your sentiments visible.

Noriko: That’s right. I conceive of my role not as one of technical cooperation, but of creating points of contact between society and people who have technology.

When I first joined the company, I wasn’t able to use heavy machinery. My father also made caustic remarks like “this is not women’s work.” Even so, I carried on with the work because I wanted to be in a position where I could convey to society my father’s sentiments in setting up the company.

When my father launched the company, he had just the one dump truck. He says that he saw the waste that was being landfilled into the sea and realized that a society in which we continue to dump waste into the sea like that would end up unsustainable at some point. His dream was to create a society in which 100% of waste can be treated.

We started by sharing my father’s sentiments with our employees. We then went on to try and share them with greater society by opening up the plant to people outside the company.

A large number of everyday people have come to visit since we opened the plant to the public. One tour participant even went so far as to say: “I’d like for your company to deal with my property after I die.”

WORK MILL: In another interview you spoke about employee work styles and said you felt it was important for employees to be able to “take pride in their own company.” Does this also relate to the idea of making your sentiments visible?

Noriko: I think that people gain confidence when they receive praise and evaluations from others. They work even harder, they learn, they gain independence. This works to strengthen governance. I believe in the soundness of mechanisms that expose the inner aspects of the company to the outside world. This creates management with a high level of transparency while also helping educate employees.

Satoyama Conservation and the Management of an Organic Farm Promote the Sharing of Sentiments

WORK MILL: I understand that in addition to the processing plant itself, you have various physical spaces including Kunuginomori Forest, and that there are many people who come to enjoy these places each day. I also heard about things you do to enhance levels of understanding in the local community, such as running an organic farm and the conservation of the wider landscape here, which can be described as satoyama, a quintessentially Japanese notion of natural environments that comprise human settlements, farmlands, and wild ecosystems. Do these kinds of initiatives contribute to the sharing of your sentiments?

Noriko:They do. These are a part of the various activities we engage in to create a close and warm emotional bond with the local community. We work to conserve the woodlands, which in the past, were hotspots for illegal dumping. We’ve been able to transform them into something close to what a satoyama environment should be.

In satoyama, people’s lives, agriculture, and forests have enjoyed a close relationship with each other since ancient times. Satoyama was a successful resource circulation model characterized by the coexistence of people and nature. We conceive of our organic farm as one kind of value creation in the resource circulation process that exists in satoyama.

Fallen leaves are composted then taken to the fields. Additional nutrients are also needed to create soil, so we also raise chickens to be able to use their droppings. The crops we harvest in these fields are then served in dishes for people to enjoy in places like Kunugi no Mori CAFE, Kunugi no Mori Bread Studio, and PIZZA-GOYA, all of which we manage. In such a way, we hope that visitors will be able to enjoy our sense of values through all their five senses.

WORK MILL: I sense some kind of similarity between the satoyama resource circulation model and Ishizaka’s circulation-related value expressed through resource recovery.

Noriko: Yes, today we have daily goods made from plastic that we have to throw away once they are past their usable life. There’s not other option. In satoyama, these kinds of objects were made from natural materials like bamboo and straw that ended up back in the ground. Nothing ended up as trash because satoyama had perfect recycling mechanisms.

Similarly, in waste treatment, our aim is 100% resource recovery. Our mission is to circulate, whether it be in the conservation of satoyama or the treatment of waste. I want to communicate the nature value represented by satoyama to the world and foster new values for the promotion of zero waste. This could be through the development of materials that are easily reused or by proposing new ways of living.

Why Do Something That’s Not Profitable? Aiming To Change the Working Environment and the Image of the Entire Industry

WORK MILL: Your opening up of the plant and your conservation of satoyama have both been received very positively. At the same time, I’m also aware that doubts have been raised about whether such initiatives are directly profitable or not.

Noriko: Making a direct profit from these may be difficult, yes. However, we believe these initiatives will serve to improve the working environment and to enhance the image of the industrial waste management industry as a whole, not only that of Ishizaka Sangyo.

Thankfully, various well-known companies from diverse industries and sectors have come to visit us, and we have also been lucky enough to receive a lot of media coverage. With this, industry peers have come to take an interest in Ishizaka Sangyo initiatives, wondering why we get so much attention even though we’re doing the same job as them.

Bit by bit, other companies in our industry will take what we have done as a reference and start to invest in education and facilities. Of course, if you make an investment, you will want to recover it and will have no option but to raise your unit price for waste treatment. Doing this will allow you to change our existing price principle culture of “the cheaper the better.”

If the salaries of employees can be raised in line with this, it will be possible to hire even better human resources and thus to also improve the quality of the service you offer.

WORK MILL: Have you observed any change in the way your industry peers think?

Noriko: I feel we’ve seen a sift in attitudes, away from the idea that there’s no problem in simply accepting and disposing of garbage and toward seeing garbage as a resource and recycling it. Also, I think that there is now a recognition that this process should be made open to the local community. In that sense, I feel we have had a positive impact on the industry.

This is the end of Part 1. In Part 2, we talk about the approach manufacturers should adopt in the coming age.

Updated: June 23rd, 2020

Date of interview: April 2020

Words: Masato Takahashi

Photos: Kensuke Oki

Images credits: Ishizaka Sangyo Co., Ltd.