Understanding Circular Economy through Japan’s Ancient Culture – Akihiro Yasui

The “circular economy,” an economic model that has gradually begun to penetrate global markets. In order for this new economic model to take root in Japan, what kind of ideologies or processes will become necessary?

Continuing from the previous segment, we spoke to Mr. Akihiro Yasui — a representative of Circular Initiatives & Partners, and a leader in circular economy research — about the differences between Japan and Amsterdam (from the perspective of the circular economy), and the surprising commonalities between Japan and the circular economy.

Previous article: Circular Economy is More Than Sustainability — Akihiro Yasui Explains Why Adopting it Helps Businesses.

Akihiro Yasui

Born in 1988. From Nerima Ward, Tokyo. Graduated from the Sustainability, Society and the Environment graduate program at the University of Kiel in Germany. Representative of Circular Initiatives & Partners. Circular economy researcher living in Kyoto. Also active as a sustainable business consultant and film creator. Lecturer at Nikkei Business School & ETIC’s 2019 “New Business & Entrepreneur Training Course for the SDG Era: Building Sustainable Cities through Resource Circulation”. Author of “Implementing Circular Economies: Exploring Business Models in the Netherlands” (Gakugei Publishing). In 2021, his spreading of the theory and implementation of circular economies throughout Japan earned him The Outstanding Young Persons 2021 Primer Minister’s Honorable Mention Award (Grand Prize).

Japan and Europe have differing “national stances.”

WORK MILL: We understand that your company Circular Initiatives & Partners is often approached by various corporations and municipalities. What kinds of inquiries have you been receiving often lately?

Yasui: Thankfully, we have been blessed with the opportunities to work together with a variety of companies and municipalities. The kinds of corporations that inquire with us are diverse and encompass a wide range of industries, such as apparel, food products, construction, and trading companies.

The inquiries we receive from these firms can range from basic questions such as “what is the difference between the circular economy and recycling and upcycling?” to questions about how the overall social transitions via public-private partnerships are progressing in Europe and the Netherlands.

Before the pandemic, there were many companies and municipalities that traveled to and participated in inspection events held in Amsterdam.

Information on the circular economy has become much more widely available than before, but we have been receiving an increase in inquiries such as “how and where should I begin in order to implement a circular economy?” or “what should I do first?”

WORK MILL: From the standpoint of the circular economy, are Japanese firms lagging behind European companies?

Yasui: Since before the term “circular economy” began to be used, there were some places in Japan that were in essence practicing a form of this model, albeit in a form that differed from how it was practiced in Europe.

In fact, it turns out that there are many aspects of these activities and mentalities in Japan that Europe has learned from. To begin with, because there are differences between Europe and Japan in the perceptions of what people judge to be “happiness,” I don’t believe that it is possible to make a sweeping statement in the vein of “Japan is behind and Europe is more progressive.”

However, the situation in Japan is that a basic understanding of the ideology of the circular economy and concurrent efforts to put it into practice in Japanese society are still lacking in terms of overall progress, so I feel that such growth will come in the future.

In any case, a big difference between Japan and Europe lies in the stances of each country. For example, the “Europe 2020” strategy proposed by the European Commission of the EU (European Union) — released in 2010 in the wake of the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers — touches upon the efficient utilization of natural resources and energy.

Furthermore, in “Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe,” released in 2011, guidelines for a circular economic society that would not be dependent on new energy sources were clearly defined. And in 2015, a long-term plan called the “Circular Economy Package” was set forth.

In response to these trends, in 2015, the Dutch government declared that it would convert its society completely into a circular economy by the year 2050. With other European countries showing signs of following suit, it appears that these societal changes are beginning to permeate the corporate world as well.

Meanwhile, the situation in Japan is that, unlike the Dutch government’s efforts, no guidelines, numerical targets, or clearly defined roadmap to develop a circular economy by 2050 have been laid out. I believe that having the government demonstrate clearly defined policies or support measures will be a major factor in getting private enterprises to accelerate their transitions to a circular economy.

On the other hand, in order to get these private companies to follow the examples set by the global marketplace, rather than waiting for the government to set policy, I feel that they should be compelled to progressively make stronger efforts to study the information coming from overseas.

WORK MILL: It appears that between Japan and Europe, there is a difference in the level of interest and commitment with their respective governments and corporations.

Yasui: That’s correct. However, in recent years, on a global level, the administrators of all industries are being compelled to address climate change and environmentally responsible efforts. Companies that don’t understand the essences of the circular economy or sustainability, or make no efforts in those areas, will undoubtedly start to find themselves facing harsh and unforgiving conditions in the future.

This is because these impacts emerge not only from how they involve themselves with the marketplace and business, but also from areas that involve financing, such as investors and banks, as well as from a legal perspective.

For example, as we can see from how “ESG investing” has gained attention, companies that don’t demonstrate concern for the environment are finding it more difficult to raise funds. What’s more, in the Netherlands, the banks have begun developing new forms of financing structures that are more compatible with circular economy business models.

Furthermore, with Europe recognizing “right to repair” as a consumer right, we are seeing an acceleration in calls for manufacturers to develop product builds and designs that are easier to repair and maintain.

In Europe, we are seeing the preparation of a framework whereby companies that do not satisfy the standards of a circular economy or sustainability will not be able to continue doing business. I predict that this will make a great impact on Japanese businesses.

Due to these various factors, Japanese firms are finding themselves compelled to take the initiative in implementing efforts toward developing a circular economy.

Examples of circular economy efforts in Japan

WORK MILL: It can be said that efforts to develop a circular economy in Japan are necessary. Are there any examples of efforts to develop a circular economy already happening?

Yasui: There are fundamental efforts already taking place in Japan. One example, which I was involved in, is the compost project undertaken by the Kurokawa Onsen Ryokan Association. Of the 30 ryokans (inns) in Kurokawa Onsen, we undertook to convert the kitchen waste produced by 8 inns into fully matured compost.

This compost was then utilized by farms in the region, to grow delicious vegetables that were then procured by the inns, and then served to their guests. The residue (*1) that resulted from the process of preparing food at the inns was processed into fully matured compost and provided to farmers. This is the type of cyclic effort which we promote.

We often hear complaints such as, “even if I convert my kitchen waste to compost, I have nowhere to use it …” If, as in the case of Kurokawa Onsen, you have these farmers who can use your compost, that would be ideal. But if you don’t have any relationships or connections that could offer similar benefits, you can combine your kitchen waste with dried leaves and rice husks, dry it out in direct sunlight, and discard it as flammable waste, which can greatly reduce your environmental impact much more than if you threw out your waste normally.

Most kitchen waste is predominantly liquid, so normal garbage incinerating facilities will use heavy oil, petroleum, or even auxiliary chemicals made of plastic, to incinerate hard-to-burn refuse.

This isn’t necessarily a circular economy approach to this problem, but merely extracting the liquid from kitchen waste by drying it can be beneficial, even if it serves merely to reduce the use of auxiliary chemicals.

*1 Food-derived garbage produced by food product-related businesses

WORK MILL: Could you provide another example of the circular economy at work in Japan?

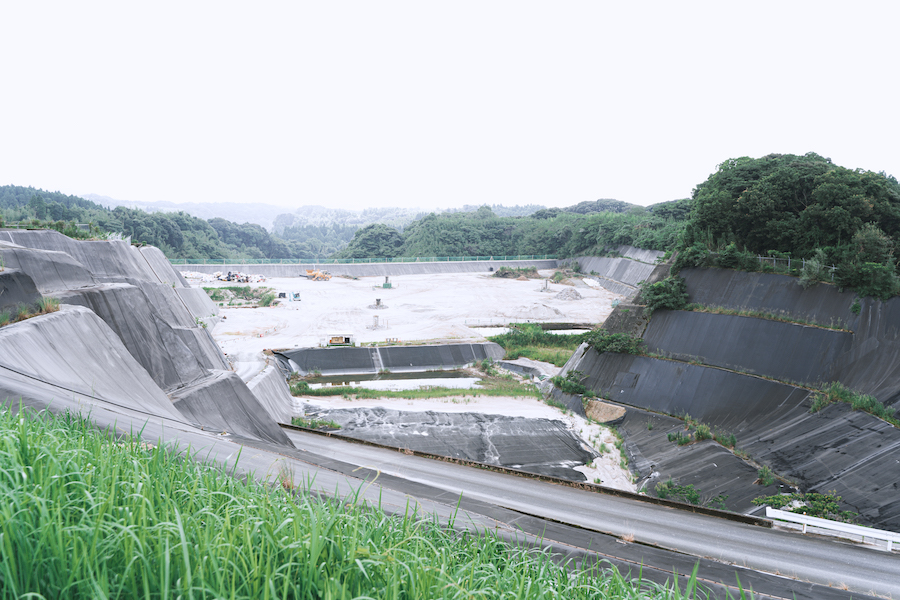

For a governmental example, I feel there is a lot we can learn from the efforts of the town of Osaki in Kagoshima Prefecture. The population of Osaki is about 12,000. Since 60% of all of the municipalities in Japan have a population that ranges from 1 to 20,000 persons, it’s understood that this town can serve as a reference model for many regions.

Osaki began a town-wide effort to develop resource circulation dating back to around 20 years ago. Currently, the town recycles over 80% of its waste, and has retained a No.1 ranking in recycling rate among all Japanese municipalities for 12 consecutive years. The town has become so famous and notable that teams from overseas have come to study their methods.

In Osaki, garbage is sorted into 27 different categories, with garbage stations managed by a resident-led “Osaki Sanitation Association.” Residents cannot discard their garbage unless they register with the association. Among the various categories of garbage, kitchen waste is collected 3 times a week, converted to fully matured compost at a composting facility, and then sold to regional farms.

The secret to corporate success is “overwhelming value and messaging”

WORK MILL: What will companies need in the future as they proceed toward developing a circular economy?

Yasui: I believe there are two factors that have led to the business success of European companies that have incorporated the circular economy model.

The first is “overwhelming value.” For example, in recent years, most of the specialty coffees that have become popular in Japan are distinguished by being produced in countries that are cultivating and managing production of their coffee beans through sustainable methods, which leads to their delicious flavors. While most of these products are being transacted at prices above fair trade value, rather than promoting that element, these coffees are attractive because a wide range of customers find appeal and value in their delicious taste and the atmospheric comfort they provide.

Meanwhile, Allbirds shoes, which are made with all natural materials, are gaining popularity throughout Japan. Allbirds shoes and specialty coffees are priced relatively more expensively than generally priced products, but because the shoes are comfortable and pleasant to wear, because the coffees taste great, these products, I feel, through their superior quality and design, possess the clues to overcoming the obstacle of price wars and leading to business success in Japan.

With that in mind, the second factor is “messaging.” The examples of success in Europe have in common a way of communicating their appeals based in messaging that is easy enough for a child to understand.

For example, this leads to the aforementioned value as well, but if you can casually message that your product is made in a clean environment, without child labor, is delicious, and is packaged so appealingly that the consumer will unconsciously find themselves reaching for it, then they will naturally find themselves recommending it to others as well. And then they will become fans of that company, and will continue to purchase that product.

On the other hand, if you were running a restaurant that used discarded food, but insistently advertised “Eradicate food waste!” or “Outlaw animal abuse!” at your front entrance, customers would recoil and avoid patronizing your business. In other words, you would be potentially limiting your business to only so-called highly conscious or politically aware clientele.

It is crucial that you communicate your message to as wide a range of consumers as possible. And in order to maintain a business, it is important that you are patronized by not only highly conscious and politically aware customers, but by the general public as well. To that end, the impression you make with your interior design or packaging has to be 95% an appealing design, while your messaging should only comprise about 5%. I believe that to be a balance that is just right.

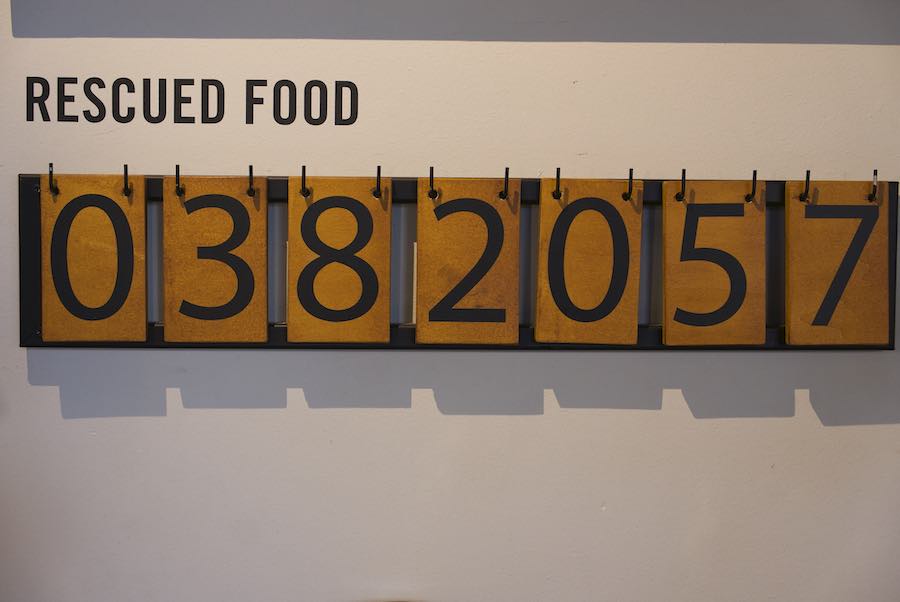

To bring up an example from the Netherlands, as I mentioned in the earlier segment, the Amsterdam restaurant Instock, which serves food prepared from food waste, does not mention terms such as “let’s get rid of food loss,” or “mottainai (wasteful).” Instead, it casually displays “statistics” in the center of the restaurant, where anybody can see them.

When I asked what those numbers meant, I was told that it was “the gross weight of all the food waste rescued by Instock since it opened.” When normal customers hear this, it becomes the first time they realize, “this is a restaurant that uses food waste,” and then they become fans. Of course, this is all predicated on the fact that the food they serve is delicious, and the restaurant atmosphere is pleasant and comfortable.

When you have something that is delicious, is beautiful, is functionally superior, and feels like a good value cost-wise, then it becomes something that you want to share with others. I feel that the ability to casually disperse messages such as being environmentally responsible and eradicating child labor in the shadow of value that is easily communicable to anyone is the key to building a business that can address and improve societal issues.

WORK MILL: There is an impression that materials and products that are eco-friendly, such as fair trade products and organic commodities, are expensive. Is there a way to change or improve this sense of cost?

Yasui: First of all, within the linear economy, I feel that it is important that we rethink our framework and ideology of overemphasizing economic rationality.

Up to now, because far and away great importance had been placed upon economic rationality in developing products and services, that triggered price wars based on mass production and mass consumption, leading to the imprinting in our minds the preconception that “any increase in price, no matter how small, will decrease sales.”

So then, is it true that products that are expensive do not sell? Not necessarily. The aforementioned specialty coffees and Allbirds shoes are expensive items, but they are very popular in Japan. The brand FREITAG from Switzerland, which sells bags made from recycled truck tarps, and the outdoor brand Patagonia, are both expensively priced, and yet Japan is a large market for them.

And then there is HERALBONY, which sells products that focus on the unique and original creativity of disabled persons. The chocolate brand kiitos, based in Kirishima, Kagoshima Prefecture, works in co-operation with disabled persons to make their products. From these companies, I think that we can learn the hints of what they share in common with companies that succeeded in Europe — design and flavor — and businesses that were able to expand in Japan — making functionality priority number one.

These brands have a message that is simple enough for a child to understand — they taste great, are well designed, and have excellent functionality. I feel that these products and manufacturers possess major clues to developing circular economy products and services in Japan.

Utilizing the benefits of Japan’s tradition for the future of society

WORK MILL: In the future, when companies start incorporating the circular economy, will consumers accept this change smoothly?

Yasui: Even in Japan, the young people of Generation Z and Millennials are showing a high level of interest in the circular economy and sustainability.

Moreover, this generation has become familiar with and cherishes the concept of “sharing” rather than individually owning things, and purchasing used products at low prices rather than buying new ones. And furthermore, instead of “purchasing things,” because the idea of “using services” through systems such as subscription models and leasing has permeated their everyday lives, I believe that they are well suited for the circular economy.

On the other hand, the elderly generation, even if they are not familiar with the Western term, “circular economy,” when given an explanation, it turns out that there are many who can relate to the concept. They say things like, “a long time ago we used to do such things regularly,” or “that way of doing things is better.”

Even with a transition to a circular economy, isn’t it likely that new products and services would be more readily welcomed than they would be now? As represented by the Edo period, when the term “mottainai” and the frameworks of recycling had been put into practice, the concept is compatible with the inherent mindset and culture of the Japanese people.

Where we should be careful is that, as we see an increase in products and services that claim to be sustainable or produced through a circular economy framework, we need to develop the knowledge and ability to be able to discern whether they indeed are what they claim to be. Even now, we are seeing cases that, upon closer inspection, turn out to be merely PR campaigns, or products that claim to be circular but turn out to be simply recycled linear economy products.

With the terms “sustainable” and “SDGs” bandied about everywhere, each and every one of us needs to deepen our understanding of the true essences of what those words mean, as well as the circumstances they entail.

On a separate note, the behavior of companies who deliberately present their products and conduct as sustainable when the facts say otherwise, is called “greenwashing.” However, greenwashing with regards to the circular economy can lead to a corporation finding themselves left behind the times, so there is a sense that it can conversely be seen as a risky move.

WORK MILL: So that means that consumers need to develop the ability to discern the essence of a circular economy. Lastly, I’d like to ask, what advice would you give to a company or individual who wants to incorporate a circular economy model.

Yasui: For individuals, rather than feeling a sense of obligation to the circular economy, that they “have to do this,” it might be better to to venture into it thinking, “doing it this way is more fun,” or “it enriches my life.” For companies, I think it’s important to have a positive, receptive attitude that “perhaps there are possibilities and opportunities for new business.”

For example, I compost my garbage at home, and because of that, it’s reduced my frequency of throwing out burnable waste, and that has made my life easier. Observing how kitchen waste is broken down on a daily basis can become a new fun routine in your daily life, and now, I’ve begun to think that perhaps I could use it to fertilize a field that I’ve recently rented in Kyoto.

While presupposing that Westerners and Japanese have different ideals about what a pleasant and comfortable society might be, we can learn from and reference the European ideology and their efforts. And it is important that we confront the issues facing Japan, as we progress toward developing a framework that is optimal for ourselves.

I feel that the ideal situation would be a society that, even without using the term “circular economy,” would implement such a framework because that was the natural, ordinary thing to do. I feel that it would be wonderful if each of us could start with something that we “want to do.”

Updated: July 6, 2022

Interviewed: August 2021

Images Provided By: Circular Initiatives & Partners, Akihiro Yasui, Totoya Inc., and unsplash.com

Interviewer: Dasha Inose (Okamura)

Text: Ayumu Kanasashi